Usuario:Friera/Taller3

En desarrollo

Se llama temperamento justo a la afinación de los instrumentos musicales siguiendo la norma de igualar la relación de las frecuencias de cualesquiera dos semitonos sucesivos. Para ello es necesario variar levemente la afinación obtenida directamente por armónicos.

An equal temperament is a musical temperament. It is a system of tuning in which every pair of adjacent notes has an identical frequency ratio. Equal temperaments are often intended to approximate some form of just intonation. In equal temperament tunings an interval - usually the octave - is divided into a series of equal steps (equal frequency ratios). For modern Western music, the most common tuning system is twelve-tone equal temperament, sometimes abbreviated as 12-TET, which divides the octave into 12 (logarithmically) equal parts. It is usually tuned relative to a standard pitch of 440 Hz.

Other equal temperaments exist (some music has been written in 19-TET and 31-TET for example, and Arabian music is based on 24-TET), but in western countries when people use the term equal temperament without qualification, it is usually understood that they are talking about 12-TET.

Equal temperaments may also divide some interval other than the octave, a pseudo-octave, into a whole number of equal steps. An example is an equally-tempered Bohlen-Pierce scale. To avoid ambiguity, the term equal division of the octave, or EDO is sometimes preferred. According to this naming system, 12-TET is called 12-EDO, 31-TET is called 31-EDO, and so on; however, when composers and music-theorists use "EDO" their intention is generally that a temperament (i.e., a reference to just intonation intervals) is not implied.

History

editarHistorically, there was Seven-equal temperament or Hepta-equal temperament practice in Ancient Chinese tradition,[1][2]. Vincenzo Galilei (father of Galileo Galilei) may have been the first person to advocate twelve-tone equal temperament (in a 1581 treatise), although his countryman and fellow lutenist Giacomo Gorzanis had written music based on this temperament by 1567. The first person known to have attempted a numerical specification for 12-TET is probably Zhu Zaiyu (朱載堉) a prince of the Ming court, who published a theory of the temperament in 1584. It is possible that this idea was spread to Europe by way of trade, which intensified just at the moment when Zhu Zaiyu published his calculations. Within fifty-two years of Chu's publication, the same ideas had been published by Marin Mersenne and Simon Stevin.

From 1450 to about 1800 there is evidence that musicians expected much less mistuning (than that of Equal Temperament) in the most common keys, such as C major. Instead, they used approximations that emphasized the tuning of thirds or fifths in these keys, such as meantone temperament. Some theorists, such as Giuseppe Tartini, were opposed to the adoption of Equal Temperament; they felt that degrading the purity of each chord degraded the aesthetic appeal of music.

String ensembles and vocal groups, who have no mechanical tuning limitations, often use a tuning much closer to just intonation, as it is naturally more consonant. Other instruments, such as some wind, keyboard, and fretted-instruments, often only approximate equal temperament, where technical limitations prevent exact tunings, other wind instruments, who can easily and spontaneously bend their tone, most notably double-reeds, use tuning similar to string ensembles and vocal groups.

J. S. Bach wrote The Well-Tempered Clavier to demonstrate the musical possibilities of well temperament, where in some keys the consonances are even more degraded than in equal temperament. It is reasonable to believe that when composers and theoreticians of earlier times wrote of the moods and "colors" of the keys, they each described the subtly different dissonances made available within a particular tuning method. However, it is difficult to determine with any exactness the actual tunings used in different places at different times by any composer. (Correspondingly, there is a great deal of variety in the particular opinions of composers about the moods and colors of particular keys.)

Twelve tone equal temperament took hold for a variety of reasons. It conveniently fit the existing keyboard design, and was a better approximation to just intonation than the nearby alternative equal temperaments. It permitted total harmonic freedom at the expense of just a little purity in every interval. This allowed greater expression through modulation, which became extremely important in the 19th century music of composers such as Chopin, Schumann, Liszt, and others.

A precise equal temperament was not attainable until Johann Heinrich Scheibler developed a tuning fork tonometer in 1834 to accurately measure pitches. The use of this device was not widespread, and it was not until 1917 that William Braid White developed a practical aural method of tuning the piano to equal temperament.

It is in the environment of equal temperament that the new styles of symmetrical tonality and polytonality, atonal music such as that written with the twelve tone technique or serialism, and jazz (at least its piano component) developed and flourished.

General properties of equal temperament

editarIn an equal temperament, the distance between each step of the scale is the same interval. Because the perceived identity of an interval depends on its ratio, this scale in even steps is a geometric sequence of multiplications. (An arithmetic sequence of intervals would not sound evenly-spaced, and would not permit transposition to different keys.) Specifically, the smallest interval in an equal tempered scale is the ratio:

Where the ratio r divides the ratio p (often the octave, which is 2/1) into n equal parts. (See Twelve-tone equal temperament below.)

Scales are often measured in cents, which divide the octave into 1200 equal intervals (each called a cent). This logarithmic scale makes comparison of different tuning systems easier than comparing ratios, and has considerable use in Ethnomusicology. The basic step in cents for any equal temperament can be found by taking the width of p above in cents (usually the octave, which is 1200 cents wide), called below w, and dividing it into n parts:

In musical analysis, material belonging to an equal temperament is often given an integer notation, meaning a single integer is used to represent each pitch. This simplifies and generalizes discussion of pitch material within the temperament in the same way that taking the logarithm of a multiplication reduces it to addition. Furthermore, by applying the modular arithmetic where the modulo is the number of divisions of the octave (usually 12), these integers can be reduced to pitch classes, which removes the distinction (or acknowledges the similarity) between pitches of the same name, e.g. 'C' is 0 regardless of octave register. The MIDI encoding standard uses integer note designations.

Twelve-tone equal temperament

editarIn twelve-tone equal temperament, which divides the octave into 12 equal parts, the ratio of frequencies between two adjacent semitones is the twelfth root of two:

This interval is equal to 100 cents. (The cent is sometimes for this reason defined as one hundredth of a semitone.)

Calculating absolute frequencies

editarTo find the frequency, , of a note in 12-TET, the following definition may be used:

In this formula refers to the pitch, or frequency (usually in hertz), you are trying to find. refers to the frequency of a reference pitch (usually 440Hz). n and a refer to numbers assigned to the desired pitch and the reference pitch, respectively. These two numbers are from a list of consecutive integers assigned to consecutive semitones. For example, A4 (the reference pitch) is the 49th key from the left end of a piano (tuned to 440 Hz), and C4 (middle C) is the 40th key. These numbers can be used to find the frequency of C4:

See Piano key frequencies for a list of 12-TET frequencies tuned to A-440.

Comparison to just intonation

editarThe intervals of 12-TET closely approximate some intervals in Just intonation. In particular, it approximates just fourths, fifths, thirds, and sixths better than any equal temperament with less divisions of the octave. Its fifths and fourths in particular are almost indistinguishably close to just. In general the next lowest viable equal temperament (as an approximation to just) is 19-TET, which has better thirds and sixths, but weaker fourths and fifths than 12-TET.

In the following table the sizes of various just intervals are compared against their equal tempered counterparts, given as a ratio as well as cents.

| Name | Exact value in 12-TET | Decimal value in 12-TET | Cents | Just intonation interval | Cents in just intonation | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unison (C) | 1.000000 | 0 | = 1.000000 | 0.0000 | 0 | |

| Minor second (C♯) | 1.059463 | 100 | = 1.066667 | 111.73 | 11.73 | |

| Major second (D) | 1.122462 | 200 | = 1.125000 | 203.91 | 3.91 | |

| Minor third (D♯) | 1.189207 | 300 | = 1.200000 | 315.64 | 15.64 | |

| Major third (E) | 1.259921 | 400 | = 1.250000 | 386.31 | -13.69 | |

| Perfect fourth (F) | 1.334840 | 500 | = 1.333333 | 498.04 | -1.96 | |

| Diminished fifth (F♯) | 1.414214 | 600 | = 1.400000 | 582.15 | -17.85 | |

| Perfect fifth (G) | 1.498307 | 700 | = 1.500000 | 701.96 | 1.96 | |

| Minor sixth (G♯) | 1.587401 | 800 | = 1.600000 | 813.69 | 13.69 | |

| Major sixth (A) | 1.681793 | 900 | = 1.666667 | 884.36 | -15.64 | |

| Minor seventh (A♯) | 1.781797 | 1000 | = 1.75 | 968.826 | -31.91 | |

| Major seventh (B) | 1.887749 | 1100 | = 1.875000 | 1088.3 | -11.7 | |

| Octave (C) | 2.000000 | 1200 | = 2.000000 | 1200.0 | 0 |

(These mappings from equal temperament to just intonation are by no means unique. The minor seventh, for example, can be meaningfully said to approximate 9/5, 7/4, or 16/9 depending on context. The 7/4 ratio is used to emphasize this tuning's poor fit to the 7th partial in the harmonic series.)

Other equal temperaments

editar5 and 7 tone temperaments in ethnomusicology

editarFive and seven tone equal temperament (5-TET and 7-TET), with 240 and 171 cent steps respectively, are fairly common. A Thai xylophone measured by Morton (1974) "varied only plus or minus 5 cents," from 7-TET. A Ugandan Chopi xylophone measured by Haddon (1952) was also tuned to this system. Indonesian gamelans are tuned to 5-TET according to Kunst (1949), but according to Hood (1966) and McPhee (1966) their tuning varies widely, and according to Tenzer (2000) they contain stretched octaves. It is now well-accepted that of the two primary tuning systems in gamelan music, slendro and pelog, only slendro somewhat resembles five-tone equal temperament while pelog is highly unequal; however, Surjodiningrat et al. (1972) has analyzed pelog as a seven-note subset of nine-tone equal temperament. A South American Indian scale from a preinstrumental culture measured by Boiles (1969) featured 175 cent equal temperament, which stretches the octave slightly as with instrumental gamelan music.

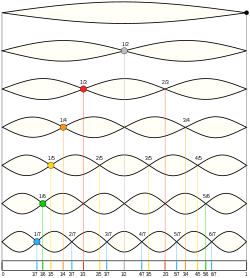

Various Western equal temperaments

editarMany systems that divide the octave equally can be considered relative to other systems of temperament. 19-TET and especially 31-TET are extended varieties of Meantone temperament and approximate most just intonation intervals considerably better than 12-TET. They have been used sporadically since the 16th century, with 31-TET particularly popular in Holland, there advocated by Christiaan Huygens and Adriaan Fokker. 31-TET, like most Meantone temperaments, has a less accurate fifth than 12-TET. It has been used in Indonesian music[cita requerida].

There are in fact five numbers by which the octave can be equally divided to give progressively smaller total mistuning of thirds, fifths and sixths (and hence minor sixths, fourths and minor thirds): 12, 19, 31, 34 and 53. The sequence continues with 118, 441, 612..., but these finer divisions produce improvements that are not audible. The explanation for this curious series of numbers lies in the denominators of fractions that approximate the logarithm to base 2 of the frequency ratios of the consonant intervals. A 2000 conjecture by Mark William Rankin, who used a computer to calculate this sequence out to a large number of terms, states that this sequence has the unusual property that each term in it can be written as the sum of the previous term and some number of other terms.[3].

In the 20th century, standardized Western pitch and notation practices having been placed on a 12-TET foundation made the quarter tone scale (or 24-TET) a popular microtonal tuning. Though it only improved non-traditional consonances, such as 11/4, 24-TET can be easily constructed by superimposing two 12-TET systems tuned half a semitone apart. It is based on steps of 50 cents, or .

41-TET is the lowest number of equal divisions which produces a better perfect fifth than 12-TET. It is not often used, however. (One of the reasons 12-TET is so widely favoured among the equal temperaments is that it is very practical in that with an economical number of keys it achieves better consonance than the other systems with a comparable number of tones.)

53-TET is better at approximating the traditional just consonances than 12, 19 or 31-TET, but has had only occasional use. Its extremely good perfect fifths make it interchangeable with an extended Pythagorean tuning, but it also accommodates schismatic temperament, and is sometimes used in Turkish music theory. It does not, however, fit the requirements of meantone temperaments which put good thirds within easy reach via the cycle of fifths. In 53-TET the very consonant thirds would be reached instead by strange enharmonic relationships. (Another tuning which has seen some use in practice and is not a meantone system is 22-TET.)

55-TET, not as close as 53 to just intonation, was a bit closer to common practice. As an excellent representative of the variety of meantone temperament popular in the 18th century, 55-TET it was considered ideal by Georg Philipp Telemann and other prominent musicians[cita requerida]. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's surviving theory lessons conform closely to such a model[cita requerida]. Based on orchestral recordings, it is evident that this intonation survived as a standard practice until about 1930.

Another extension of 12-TET is 72-TET (dividing the semitone into 6 equal parts), which though not a meantone tuning, approximates well most just intonation intervals, even less traditional ones such as 7/4, 9/7, 11/5, 11/6 and 11/7. 72-TET has been taught, written and performed in practice by Joe Maneri and his students (whose atonal inclinations interestingly typically avoid any reference to just intonation whatsoever).

Other equal divisions of the octave that have found occasional use include 15-TET, 34-TET, 41-TET, 46-TET, 48-TET, 99-TET, and 171-TET.

Equal temperaments of non-octave intervals

editarThe equal tempered version of the Bohlen-Pierce scale consists of the ratio 3:1, 1902 cents, conventionally a perfect fifth wider than an octave, called in this theory a tritave, and split into a thirteen equal parts. This provides a very close match to justly tuned ratios consisting only of odd numbers. Each step is 146.3 cents, or .

Wendy Carlos discovered three unusual equal temperaments after a thorough study of the properties of possible temperaments having a step size between 30 and 120 cents. These were called alpha, beta, and gamma. They can be considered as equal divisions of the perfect fifth. Each of them provides a very good approximation of several just intervals.[2] Their step sizes:

- alpha: (78.0 cents)

- beta: (63.8 cents)

- gamma: (35.1 cents)

Alpha and Beta may be heard on the title track of her 1986 album Beauty in the Beast.

See also

editarSources

editar- Burns, Edward M. (1999). "Intervals, Scales, and Tuning", The Psychology of Music second edition. Deutsch, Diana, ed. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-213564-4. Cited:

- Ellis, C. (1965). "Pre-instrumental scales", Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 9, 126-144.

- Morton, D. (1974). "Vocal tones in traditional Thai music", Selected reports in ethnomusicology (Vol. 2, p.88-99). Los Angeles: Institute for Ethnomusicology, UCLA.

- Haddon, E. (1952). "Possible origin of the Chopi Timbila xylophone", African Music Society Newsletter, 1, 61-67.

- Kunst, J. (1949). Music in Java (Vol. II). The Hague: Marinus Nijhoff.

- Hood, M. (1966). "Slendro and Pelog redefined", Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology, Institute of Ethnomusicology, UCLA, 1, 36-48.

- Temple, Robert K. G. (1986)."The Genius of China". ISBN 0-671-62028-2

- Tenzer, (2000). Gamelan Gong Kebyar: The Art of Twentieth-Century Balinese Music. ISBN 0-226-79281-1 and ISBN 0-226-79283-8

- Boiles, J. (1969). "Terpehua though-song", Ethnomusicology, 13, 42-47.

- Wachsmann, K. (1950). "An equal-stepped tuning in a Ganda harp", Nature (Longdon), 165, 40.

- Cho, Gene Jinsiong. (2003). The Discovery of Musical Equal Temperament in China and Europe in the Sixteenth Century. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press.

- Jorgensen, Owen. Tuning. Michigan State University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-87013-290-3

- Surjodiningrat, W., Sudarjana, P.J., and Susanto, A. (1972) Tone measurements of outstanding Javanese gamelans in Jogjakarta and Surakarta, Gadjah Mada University Press, Jogjakarta 1972. Cited on http://web.telia.com/~u57011259/pelog_main.htm, accessed May 19, 2006.

- Stewart, P. J. (2006) "From Galaxy to Galaxy: Music of the Spheres" [3]

Notes

editar- ↑ http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/qikan/periodical.Articles/ZHONGUOYY/ZHON2004/0404/040425.htm Findings of new literatures concerning the hepta - equal temperament

- ↑ http://scholar.ilib.cn/Abstract.aspx?A=xhyyxyxb200102005 "七平均律"琐谈--兼及旧式均孔曲笛制作与转调

- ↑ [1]

External links

editar- Explaining the Equal Temperament

- An Introduction to Historical Tunings

- A beginner's guide to temperament

- Huygens-Fokker Foundation Centre for Microtonal Music

- Telemann's New Musical System

- A.D. Fokker: Simon Stevin's views on music

- Music of Sacred Temperament

- A.Orlandini: Music Acoustics

- "Temperament" from A supplement to Mr. Chambers's cyclopædia (1753)

- Tuned Piano - a web piano tuned to equal temperament.

- 12TET Frequency Table Maker - Creates a frequency table (Hz.) for all 12TET pitches

Jose Yglesias was a Cuban American novelist (born in 1920, died in New York November 8, 1995)[1]

Biography

editarYglesias was born in the Ybor City section of Tampa, Florida and was of Cuban and Spanish descent.

He moved to New York City at the age of 17 and served in the United States Navy during World War II. He studied at Black Mountain College and was a film critic for The Daily Worker. He lived in New York City and North Brooklin, Maine. For more than 10 years he was an executive for the pharmaceutical company Merck, Sharp & Dohme.[1]

Yglesias was the patriarch of a writing family, which in addition to his son, the novelist and screenwriter Rafael Yglesias, included his wife, Helen Yglesias, a novelist as well.

Jose Yglesias died on November 7, 1995 at Beth Israel Hospital in New York City from cancer.[1]

He published eleven books: seven novels and four works of nonfiction. He also wrote articles for The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine and other periodicals.

Works

editar- A Wake in Ybor City (1973), about Cubans who immigrated to Florida.

- The Goodbye Land (1967), about Galicia, his father's native province in Spain.

- In the Fist of the Revolution (1968), an intimate view of Mayari, a small country town in Cuba, under the rule of Fidel Castro.

- Down There, deals with the lives of people in Brazil, Cuba, Chile and Peru.

- The Franco Years (1975), a series of interviews, with people who lived in Spain under Francisco Franco's dictatorship.

- An Orderly Life

- Double Double

- The Truth About Them

- The Kill Price

- Home Again,

- Tristan and the Hispanics (1989), centered on a man who was the most famous Latin American writer of his generation.

[[Categoría:Terminología musical]]

- ↑ a b c «Jose Yglesias, Novelist of Revolution, Dies at 75.A version of this obituary; biography appeared in print on November 8, 1995, on page B20 of the New York Times (New York edition)». The New York Times. Consultado el 13 de enero de 2010.